‘We’ve constrained play and forced it into games. I would like to liberate play from games.’—Miguel Sicart.

Here’s an interesting premise: that games—and, in particular, videogames—incarcerate play. That play increasingly has become subject to commodification. Play as the product of games or, as Miguel Sicart suggests, play as a sausage disgorged from the ‘sausage machine’ of commercial game development.

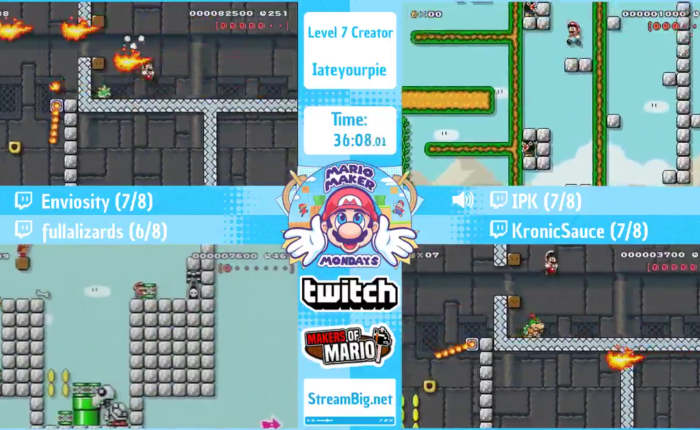

In this short series of posts, I will attempt to collate my reactions to a number of readings I’m doing in preparation for a talk I’m giving next month. A talk about SMM of course, but also about histories of play and design. How, in this instance, my story of SMM (if not Mario Maker Mondays in particular) is one informed by two, quite contrastive, percursory tales: Nintendo’s own (or, at least, how it has been written as such); and the much less visible, oft ignored, tales from the trenches of the “illegal” speedrunning and ROM hacking communities. An official versus unofficial fables of Mario.

I begin by drawing upon a series of three articles appearing in a special edition of the Journal of Games Criticism which collates a series of papers from the Extending Play: The Sequel conference held at Rutgers University, 17-8 April 2015.

First up, Anne Gilbert’s interview with Miguel Sicart and Anna Anthropy entitled ‘Liberating Play’.

As introduced above, both Anna and Miguel are fearful of what appears to be a trend within game studies, a (cynical) move towards the ludification of our cultures. Here Anna and Miguel draw upon a recent debate instigated by Eric Zimmerman’s Manifesto for a Ludic Century circa 2013, a debate that is difficult to effectively summarise here but one that most certainly displaced much water in its wake. The crux, as I see it, is an overarching concern that many approaches to the study of games (most notably the formalist discourse) privilege the object over its action — what a game is over what a game does for example. That somehow, by applying game design techniques to the modelling (measuring) of our “real” world situations (through simulation) will expose the architectures (and architects) of their design. That somehow, by exposing these mechanisms for what they truly are, we, the laypeople, will be magically transformed into the designers of our own destinies which, in turn, will enable us to collectively alter our habits and activities forming new patterns and identities that will inevitably reshape our societies for the betterment of us all. Certainly, an overly deterministic view if nothing else.

The criticisms are numerous, mainly orienting around the fact that everything game-like may not be best understood through methods of analysis and process — quantified, measured, hanged, drawn and quartered. That doing so may only count want can be counted, not necessarily what may actually count (as William Bruce Cameron might have once said). I can’t help but draw parallels between this debate and age-old discussions that attempt to differentiate between games and play (games as a subset of play, play as a subset of games) which are, for me, irresolvable conflicts often dependent upon for whom the answer serves and from whose perspectives it draws from. Nevertheless, games cannot be reduced to, nor best captured via datasets cast in the mould of optimal and maximal return, as Anna contends:

There’s a really formalist discourse around games. It focuses on quantitative and technical games. When you consider this really mathematical and formalist idea of games, it leaves out a lot of the work that marginalized play and game designers are doing: Work that doesn’t fit the quantitative and competitive model of games.

I guess the question for me is that we play both within the systems of games—we collectively agree to abide by its rules and structures insomuch as by doing so we make possible the game-as-it-to-be-played—as much as we play with games and reconfigure them through creative, playful acts of modification and self-expression. All in all, how we do so via what means notwithstanding, we converse through play.

Whether we choose to playfully engage with our “real’ world or not (to approach our world as a set of systems to be played with, or not) must be a choice that we make. To play is a decision that is ours alone to make. If not, and we do not engage with consent, then play it cannot be. Certainly, the what, when, where, and how we play should not be determined by some quantitative measures within allocated timeframes, nor circumscribed by anyone else. As Anna contends:

We’ve compartmentalized play. We’ve compartmentalized play in a way that’s consistent with the structure of capitalism. We have a time for work and a time for play. We have safe, predetermined spaces of play.

The games we play are not sausages from a sausage machine.

I’m inclined to see videogames as an abstraction: as Chaim Gingold attests, videogames are ‘miniature worlds’ designed to engender wonder and enchantment. These virtual (read fictive) worlds afford the means for us to approach situations from perspectives other than our own and to share these experiences with others. Whilst I feel it deeply unlikely that ludification and its promise will ever equip us with the means to peel back the metaphorical layers of our reality granting us a direct and unmediated access to the matrix within, I am, however, tempted to suggest that playfulness (and all of its incongruencies and inconsistencies) may be just the right kind of tonic required to render visible the ideologies behind those that are inclined to present our world as “ludified” and knowable as such. To peer, metaphorically speaking, not only behind the curtain but also behind the theatre itself.

I see gameplay as a liminal experience. One that is all too ready to reveal the artifice of its creation. To reveal its secrets as a system that is false. An abstraction, a magic crayon, a dolls house, or, even, a toy. Exploring the boundaries of these systems (to discover and to probe, to reveal and to share) is what is interesting about videogames. Playing, not necessarily abiding by the systems and structures therein, but rather toying with them. Pushing outwards towards (and hopefully beyond) the confines themselves. To break, tinker, remix, and fake videogames. These are the predicates of our interactions: creative, playful modes of engagement that recast our computational media as the tools for self-expression that they always already were. As Anna contends, it is worth noting how the practice of tinkering has very much been written out of our everyday use of computers, commerce having repressed these expressive tools into mere consumer products:

The creativity has been designed out of computers in a lot of ways. It was a really deliberate effort to change the user base of computers from tinkers to consumers.

This is why I draw great affinity with Anna’s opening gambit and their desire to distance themselves from the label ‘game designer’ towards ‘play designer’ instead. To move away from seeing play as a product (of games), instead to reclaim play as the interactions between people; their activities, performances, and practices. Play as a form of communication. To design; a practice that creates our tools to communicate with:

The discourse around play—especially in academic spaces—privileges games, and particularly video games. It embraces the idea of play as product, and not the broad range of ways that we interact with people through play. In this turn, we lose both the expressiveness of play, and a rich cultural and ritual history that predates game technology.

[…]

We need to view technology as an integrated part of play, instead of its source. In my own work, I’ve been thinking of games as experiences, instead of as media— performances. For me, this is a more interesting way to think about the kind of interactions that people have together around games.

Miguel takes a similar stance, albeit one that focuses on the label ‘games scholar’ and its ramifications:

A games scholar cannot look at people, they cannot look at communities, they cannot look at babies, they cannot look at playgrounds [sic] toys. A games scholar cannot look at all of the things that we, as humans, do while we are playing.

Although I appreciate the sentiment behind Miguel’s opinion when alluding to this schism between games and play that must be bridged, games scholars most certainly have and do look at all these things, depending on their (chosen discipline and) approach taken. My list is far from exhaustive (and my reading of them even less so) but Taylor, Pearce, Giddings, Dovey and Kennedy, Newman, for me, all prioritise the acts of playing over the game itself.

Perhaps Miguel is right to resort to hyperbole as a deliberate way to highlight how such approaches to the study of videogames have been marginalised (which is certainly true within mainstream games criticism) to the point of becoming invisible. None more so than within videogame histories it seems, with its inclination to fetishise material objects as the more easily obtained, returnable and archivable documents, rather than approach the far more challenging task of developing methods suitable to adequately account for the multiplicities of these media performances — in this case, the elusive, transient, situated practices or playings of videogames. Or, as Miguel puts it:

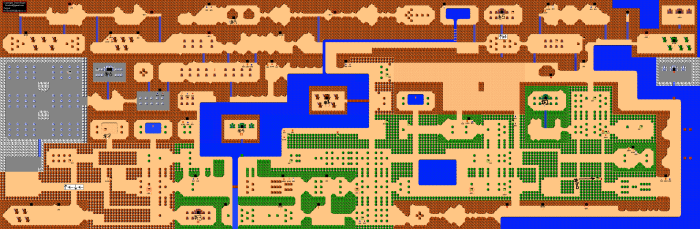

It’s always been difficult to write a history of play because it’s transcendent—it vanishes over time. The only things that we have to hold onto are the objects that it leaves behind. Those, typically, are games, toys, and the spaces that we play in. The problem is that we fetishize video games—an object. It’s a disservice to what computers can be, in the context of play, that we fetishize games in this particular way. There is no history of play because we fetishize what the video game object is.

This reifying or concretizing of our cultures is nothing new, something archival practices and historical methods have been “doing” to our collective histories for hundreds of years now (and with much graver consequences than are being addressed here). For what is lost via such translation is telling, as Anna mentions whilst discussing their book entitled ZZT which itself puts forward an account of a ‘submerged continent’ of shareware game designers:

It’s sad to me that so much history is being lost, just because we’re not paying attention. My most recent book was specifically about these ephemeral communities, it’s called ZZT. It’s about the communities of sharer games designers in the 90s. Those sorts of communities have fallen off the established history of games, which is really corporate-centric. It’s about Nintendo, about Sega, about the people who won. […] Unfortunately, our history watches over these stories, in an effort to idealize an elite few working for giant corporations.

Miguel adds to this by questioning the validity of venerating hero designers, seeing authorship as the misstep in our retellings of play:

It’s also a challenge for historians to write the proper history of video games. All these communities and games matter, but how can we learn about them? We need to abandon this idea of authorship. It makes no sense in the context of games. We should talk about the organizers of communities, but that’s not how we document games.

“[H]ow we document games.” Perhaps I should adopt this as the subtitle of my doctoral thesis. For now, however, what it eludes to feeds directly into my preparation for the presentation I’m delivering in a couple of weeks: how Mario’s history does not necessarily belong to Nintendo.